Walk into the Bank of England Museum and you’re not just stepping inside a building-you’re walking through 325 years of money, power, and panic. This isn’t a place with dusty coins behind glass. It’s where Britain’s economy was shaped, crises were handled, and the idea of money itself changed forever. If you’ve ever wondered how a piece of paper became worth more than gold, or why a bank run can shake a city, this museum tells you in real stories, real objects, and real human choices.

What You’ll See Inside the Bank of England Museum

The museum sits right where the Bank of England was founded in 1694, tucked between the narrow alleys of the City of London. You won’t find grand marble halls here. The building’s old, cramped, and full of character-just like the financial system it once ran. The exhibits are arranged like a timeline of money’s evolution, and they don’t hold back.

One of the first things you’ll notice is the Bank of England Museum’s original 18th-century gold vault. Not a replica. The real thing. Thick iron doors, hand-forged locks, and a floor that still creaks under the weight of centuries. You can stand where clerks once counted bars of gold by candlelight, knowing one mistake could mean ruin. There’s a scale from 1720, still marked with the weight of the South Sea Bubble’s collapse. That’s not just history-it’s a warning.

Then there’s the 1930s banknote printing room. You can see the actual presses that printed £1 and £5 notes during WWII. The ink was mixed with a special dye to prevent counterfeiting. Workers had to wear gloves to avoid leaving fingerprints. A sign from that era reads: “If you see something suspicious, report it immediately.” It’s chilling how little has changed.

The Money That Shaped London

London didn’t become a global financial hub by accident. The Bank of England was the engine. When the Napoleonic Wars drained the treasury, the Bank issued war bonds. When the Industrial Revolution needed capital, it lent to railroads and factories. When the Great Depression hit, it was the Bank that tried to hold the pound steady-even as unemployment soared.

The museum shows you the 1949 devaluation of the pound from $4.03 to $2.80. It wasn’t just a number. It meant British families suddenly had less buying power. Imported food got more expensive. Factories cut shifts. The Bank’s governor at the time, Sir John Cadman, said in a private memo: “We are not devaluing money. We are devaluing our expectations.” That line is displayed in the museum. It’s one of the most honest things ever written about economics.

There’s also a display on the 1971 switch from pounds, shillings, and pence to decimal currency. Kids in 1971 had to learn a whole new way to count money. The Bank printed 100 million leaflets explaining “10 new pence equals one shilling.” Those leaflets are here, yellowed and folded. You can see a child’s handwriting on one: “Why can’t we just keep shillings?”

How the City’s Heritage Lives in the Museum

The Bank of England isn’t just a museum-it’s a living piece of the City of London’s identity. The City isn’t a neighborhood. It’s a financial district with its own mayor, police force, and traditions dating back to medieval guilds. The Bank sits at its heart, surrounded by centuries-old buildings that still house trading floors, insurance firms, and private banks.

Walk outside the museum, and you’re surrounded by heritage. The Royal Exchange, built in 1566, is a five-minute walk away. Lloyd’s of London, where insurance was invented, is just around the corner. The old Stock Exchange building, now a hotel, still has its original trading bell. These places aren’t tourist traps. They’re working institutions with deep roots.

The museum connects you to all of it. A touchscreen map shows you how the Bank’s interest rate decisions in 1992-when George Soros bet against the pound-rippled across the City. You see the same streets where traders ran during the 2008 crash. You hear audio clips of bank clerks describing the 1987 Black Monday crash. It’s not about numbers. It’s about people.

Interactive Displays That Make History Click

Most museums let you look. This one lets you do.

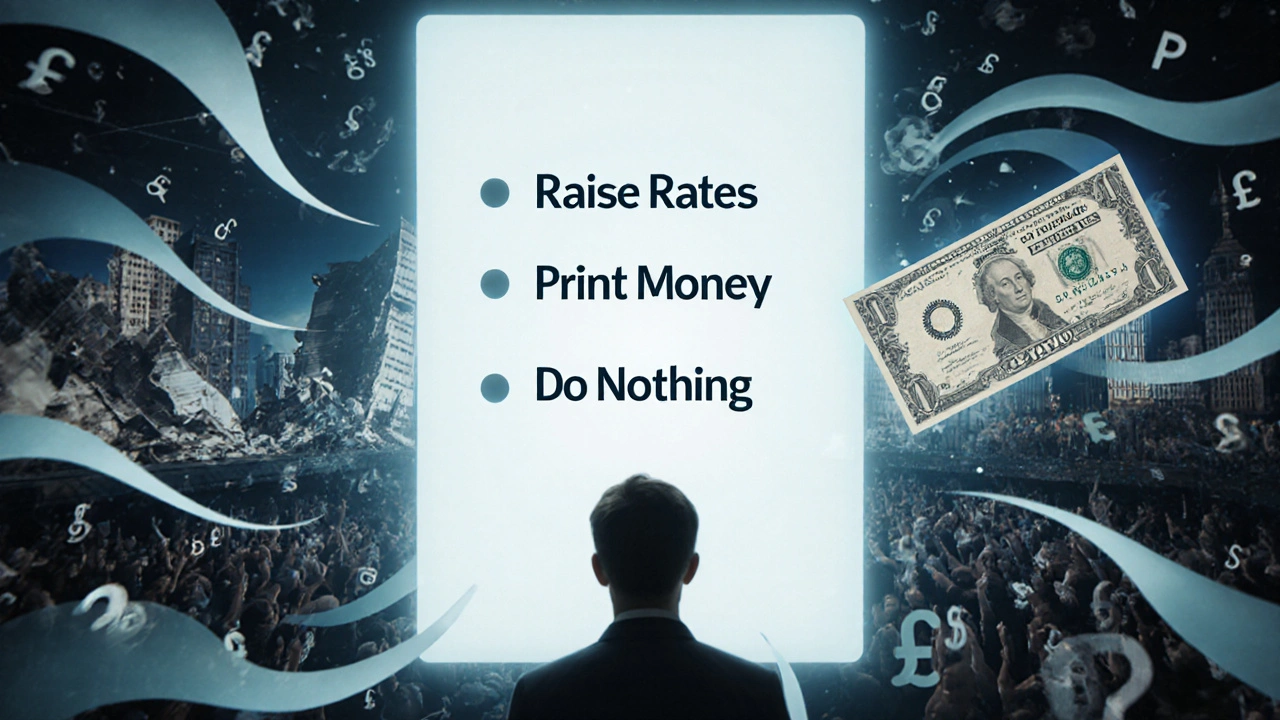

There’s a simulator where you play the role of Bank of England governor during a financial crisis. You get three choices: raise interest rates, print more money, or do nothing. Each choice triggers a different outcome-recession, inflation, or panic. I tried it three times. Each time, I lost control of the economy by minute 12. It’s humbling. No one has all the answers.

Another exhibit lets you hold a replica of the first £1 note, printed in 1797. It’s smaller than a modern credit card, handwritten, and signed by two clerks. You can turn it over and see the watermark: “I promise to pay the bearer on demand the sum of one pound.” That promise? It’s still on every pound note today. Just without the handwriting.

There’s even a “Counterfeit Detector” station. You’re given five notes-some real, some fake-and you have to pick the fakes using only a magnifying glass and UV light. Most people get three wrong. The real ones have tiny details: a thread woven into the paper, a micro-printed image of the Queen’s face, a watermark only visible when held up to light. These aren’t security features. They’re art.

Why This Matters Today

People think money is digital now. Cards, apps, crypto. But the rules were written here. The idea that a central bank can control inflation? That started here. The concept of a lender of last resort? Invented here. The panic that spreads when people lose trust in money? Seen here, over and over.

The museum doesn’t glorify finance. It shows its flaws. The 1825 banking crisis wiped out 70 banks in six months. The 1929 crash started here. The 2008 bailout? The Bank’s emergency notes were printed in secret and flown to banks in armored vans. You can see the flight manifest in the exhibit.

What you walk away with isn’t a sense of awe for big banks. It’s respect for the fragile system that keeps things running. Money doesn’t have value because it’s printed. It has value because people believe it does. And that belief? It’s been tested, broken, and rebuilt here for more than three centuries.

Visiting Tips

The museum is free to enter, open Tuesday to Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. No booking needed unless you’re with a group of 15 or more. The building is accessible, with lifts and audio guides in 10 languages. Don’t miss the gift shop-they sell replica gold bars (real metal, not plastic) and old banknotes framed in glass.

Go on a weekday if you want space. Weekends get crowded. Bring a notebook. The exhibits are dense. You’ll want to remember what you saw.

After the museum, walk to the nearby Guildhall. There’s a free exhibition on the Great Fire of London and how the City rebuilt its finances after it. Then grab a coffee at The Bank Coffee House, just across the street. It’s in a 17th-century merchant’s house. The barista knows the history. Ask her about the 1720s. She’ll tell you stories no guidebook has.

Is the Bank of England Museum worth visiting?

Yes-if you’re curious about how money works, how crises happen, or why London became a global financial center. It’s not just for finance nerds. The exhibits are hands-on, emotional, and surprisingly human. You’ll leave with a deeper understanding of why your paycheck, your mortgage, and your savings matter in ways you never thought about.

How long does a visit to the Bank of England Museum take?

Most people spend 60 to 90 minutes. If you’re really into history or want to try every interactive display, you could spend two hours. There’s no rush. The museum is designed for quiet exploration, not crowds.

Can you see the Bank of England’s actual gold vaults?

Yes. The museum includes a walk-through of the original 18th-century gold vault where Britain’s reserves were kept. It’s not the main vault used today-that’s underground and highly secure-but this one is real, untouched, and still holds some of the original gold bars. You can see the iron doors, the marks from the chains used to move the bars, and even the fingerprints left by 19th-century clerks.

Is the museum suitable for children?

Absolutely. The interactive exhibits-like the crisis simulator and counterfeit detector-are designed for kids. There’s a family trail with fun challenges, and free activity packs for ages 6-12. One child I met there said, “I thought money was just paper. Now I know it’s like a game where everyone has to believe in it.” That’s the whole point.

Are there any special events or temporary exhibits?

Yes. The museum rotates exhibits every 6-8 months. In 2024, they had “The Digital Pound: Can Money Be Code?” exploring central bank digital currencies. In early 2025, they launched “Money and War: How Finance Fought WWII,” featuring letters from soldiers paid in banknotes, ration books, and a 1944 emergency printing press. Check their website before you go-each exhibit is deeply researched and rarely seen elsewhere.

What to Do After Your Visit

Once you’ve walked through the museum, the City of London opens up. The Tower of London is a 15-minute walk-where kings once stored treasure before the Bank existed. St. Paul’s Cathedral, rebuilt after the Great Fire with money raised by a national tax, is nearby. The Monument to the Great Fire stands just steps from the Bank, marking where the fire started.

There’s also the Museum of London Docklands, a short tube ride away, which shows how global trade funded the Bank’s rise. Or head to the Guildhall Art Gallery to see paintings of 18th-century bankers-men in wigs, holding ledgers like weapons.

Don’t rush. The City doesn’t shout. It whispers. And if you listen, you’ll hear the echoes of every financial decision that shaped modern Britain.