Walk through Bloomsbury on a crisp autumn morning, and you’ll feel like you’re stepping into the pages of a novel. The quiet squares, the red-brick townhouses, the small blue plaques nailed to walls-they’re not just decorations. They’re signposts to the lives of writers who changed literature forever. This isn’t a tour of grand monuments. It’s a quiet, intimate journey through the places where Virginia Woolf scribbled her first drafts, where George Bernard Shaw argued over tea, and where Charles Dickens once walked the same pavements you’re standing on right now.

The Heart of Bloomsbury: Russell Square and the Literary Circle

Russell Square is the anchor of this walk. Its wide lawns and mature trees were the daily escape for writers who lived in the surrounding terraces. In the early 1900s, this square became the unofficial headquarters of the Bloomsbury Group. You won’t find a museum here, but you’ll find the energy of ideas. Virginia Woolf and her brother Thoby lived just a few doors down from artist Duncan Grant. Lytton Strachey, the biographer who shattered Victorian hagiography, walked these paths every morning. Their conversations didn’t happen in lecture halls-they happened over boiled eggs and weak tea in rented rooms.

Look up at number 46, Russell Square. That’s where Woolf lived from 1907 to 1911. The house is private now, but the blue plaque on the wall tells you what you need to know: Virginia Woolf 1882-1941, writer, lived here. It’s simple. No grand ceremony. Just the truth. That’s how Bloomsbury worked-real work, real lives, no fanfare.

46 Gordon Square: Where the Bloomsbury Group Took Shape

Walk two blocks south to Gordon Square. At number 46, the Bloomsbury Group held its first serious meetings. This was the home of Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister, and her husband Clive Bell. In 1904, after their father’s death, the Woolf siblings moved here from South Kensington. The house became a laboratory for modern thought. They talked about art, feminism, sexuality, and the future of the novel. E.M. Forster came often. John Maynard Keynes dropped by between economic theories. They didn’t have a manifesto. They just talked-and wrote.

The building is now part of the University of London. You can’t go inside, but the blue plaque on the front wall says it all: The Bloomsbury Group met here. That’s it. No dates. No names. Just the fact that something extraordinary happened here. That’s the power of these plaques-they don’t tell you what to think. They just say: this is where it happened.

22 Fitzroy Square: George Bernard Shaw and the Realist Playwright

Head west to Fitzroy Square. At number 22, George Bernard Shaw lived from 1905 to 1938. He didn’t write plays here-he wrote pamphlets, letters, and critiques. Shaw was a socialist, a critic, and a provocateur. He once said, “The reasonable man adapts himself to the world; the unreasonable one persists in trying to adapt the world to himself. Therefore all progress depends on the unreasonable man.” That’s the spirit of this place.

His blue plaque calls him a playwright and critic. That’s accurate, but it doesn’t capture the full weight of his influence. He turned theater into a platform for social change. Plays like Pygmalion and Man and Superman didn’t just entertain-they challenged class, gender, and education. You can still see the original wrought-iron gate he used to slam when he stormed out after arguments. It’s still there.

48 Doughty Street: Charles Dickens and the Ghosts of London

Now walk south to Doughty Street. This is where Charles Dickens lived from 1837 to 1839. He wrote Oliver Twist here. He wrote Nicholas Nickleby here. He walked the streets of London with a notebook in his pocket, listening to street vendors, watching the poor, recording the voices of the forgotten. This house is now the Dickens House Museum, the only preserved home of Dickens in London.

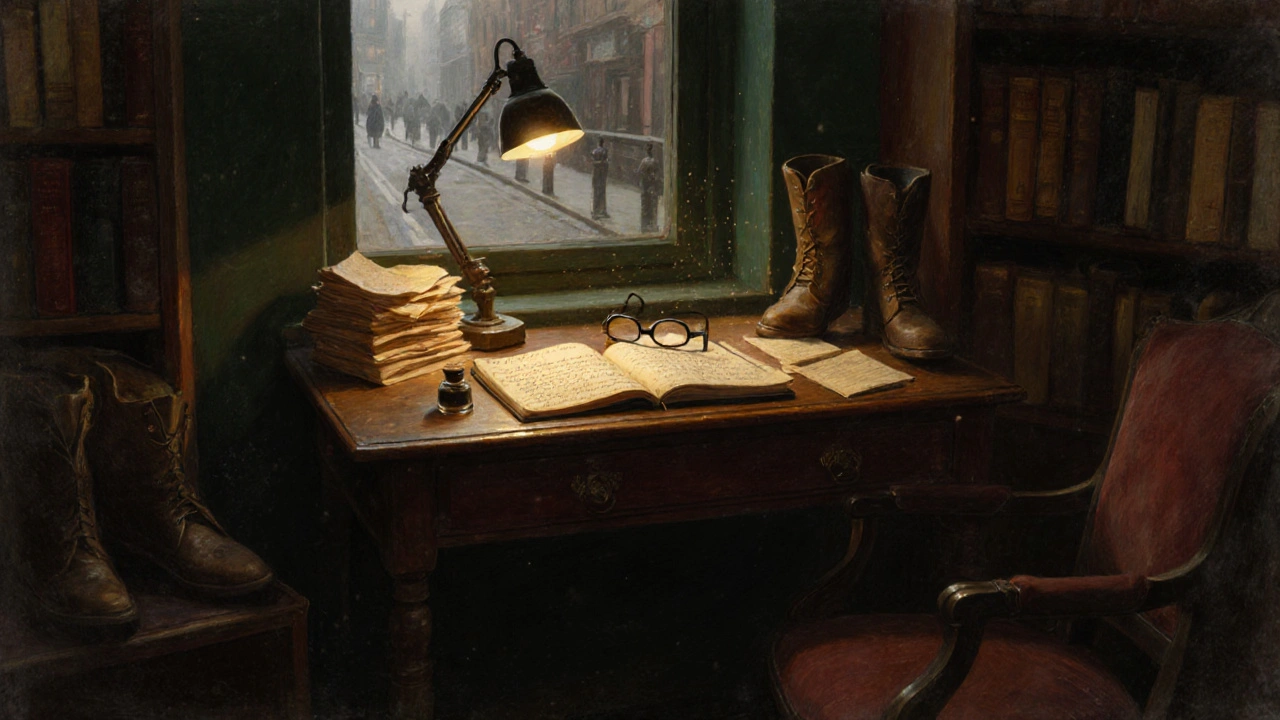

Step inside, and you’ll find his writing desk. It’s small. The inkwell is dry. The chair is worn. He wrote 800 words a day, every day, even when he was sick. He’d walk five miles through London just to clear his head. That’s how he found his characters-not in libraries, but on the streets. The museum doesn’t just show his books. It shows his process. His boots. His reading glasses. The list of names he jotted down for future characters. This isn’t a shrine. It’s a workshop.

29 Fitzroy Square: E.M. Forster and the Quiet Revolutionary

Back to Fitzroy Square, but this time to number 29. E.M. Forster lived here from 1910 to 1912. He wrote A Room with a View while sitting at this window. He didn’t write about revolutions or wars. He wrote about the quiet moments when people changed-when a woman dared to say no, when a man finally spoke his truth. His blue plaque says novelist. That’s all it needs to say.

Forster was gay in a time when it was illegal. He couldn’t write openly about love between men. So he wrote about longing. About missed chances. About the weight of silence. He lived here quietly. He didn’t host parties. He didn’t give speeches. He just wrote. And his books became the quiet rebellion of a generation.

The Blue Plaque System: How London Honors Its Writers

London has over 900 blue plaques. Only 80 of them honor writers. That’s not because writers were unimportant-it’s because the system was designed by the Royal Society of Arts in 1866 to mark places where significant people lived and worked. The plaques are small. They’re not gilded. They don’t glow. They’re just blue ceramic with white lettering. That’s intentional. They’re meant to be noticed by those who look.

Each plaque is approved by a panel. They don’t pick celebrities. They pick influence. Did this person change the way we think? Did their work survive? Did they live here long enough to be shaped by the place? Virginia Woolf? Yes. Oscar Wilde? No-he never lived in Bloomsbury. He lived in Chelsea. That’s why you won’t find his plaque here.

The plaques aren’t about fame. They’re about presence. They say: someone important lived here. And their ideas changed the world.

Why This Walk Matters Today

In 2025, we live in a world of noise. Algorithms feed us headlines. Social media shouts at us. We’re told to consume, to react, to share. But in Bloomsbury, the writers didn’t chase attention. They chased truth. They wrote in silence. They walked alone. They argued over tea. They read each other’s drafts. They didn’t need to be seen. They needed to be heard.

Walking this route isn’t about nostalgia. It’s about remembering how ideas grow. Not in boardrooms. Not in viral posts. But in quiet rooms, over years, with stubborn dedication. You don’t need a degree to walk this path. You don’t need to have read To the Lighthouse. You just need to stop for a minute. Look at the plaque. Think about the person who sat in that chair. And ask yourself: what will your quiet work leave behind?

Are all the houses on the Bloomsbury Literary Walk open to the public?

No, most of the houses are private residences or part of university buildings. Only the Dickens House Museum at 48 Doughty Street is fully open to visitors. The other locations have blue plaques you can view from the street. You can’t go inside, but you can stand where they stood and imagine the work that happened there.

How many blue plaques are there in Bloomsbury?

There are about 15 blue plaques in the Bloomsbury area, with 8 directly linked to writers. The rest honor scientists, politicians, and artists. The most important ones for literary fans are at Russell Square, Gordon Square, Fitzroy Square, and Doughty Street.

Can I visit the Bloomsbury Literary Walk in one day?

Absolutely. The entire walk-from Russell Square to Doughty Street-is less than 2 miles. It takes about 2.5 hours if you stop at each plaque, read the signs, and sit for a coffee in one of the nearby cafés. Wear comfortable shoes. Bring a notebook. And don’t rush. The point isn’t to check boxes. It’s to feel the rhythm of the place.

Is the Bloomsbury Literary Walk suitable for children?

Yes, if you make it a story hunt. Kids love finding plaques like treasure. Bring a printed map or use the English Heritage app. Turn it into a game: “Who wrote the most books?” “Who lived here the longest?” “Which writer had the weirdest habit?” The history becomes alive when you make it personal.

What’s the best time of year to walk this route?

Autumn is ideal. The leaves turn gold over Russell Square, and the air is crisp. Spring is nice too, with flowers blooming in the gardens. Summer can be crowded. Winter is quiet but cold-perfect if you like solitude. Avoid bank holidays. The museum gets packed, and the streets fill with tour groups.

Next Steps: What to Do After Your Walk

After you finish the walk, head to the British Library. It’s just a 10-minute walk from Doughty Street. They have original manuscripts of Woolf’s novels, Dickens’s letters, and Shaw’s handwritten edits. You can see the ink smudges, the crossed-out lines, the coffee stains. It’s proof that genius isn’t magic. It’s work.

Or stop by the Bloomsbury Bookshop on Charing Cross Road. It’s small, cluttered, and run by a woman who’s read every book on the shelf. Ask her for a recommendation. She’ll give you one that changes your life.

Or just sit on a bench in Gordon Square. Watch the students rush by. Listen to the wind in the trees. And remember: the next great book might be written in a room just like this one. All it needs is someone willing to sit down and write.